Volunteers surveying the lowest spoil heap and working area at Fairfield iron mine in 2013

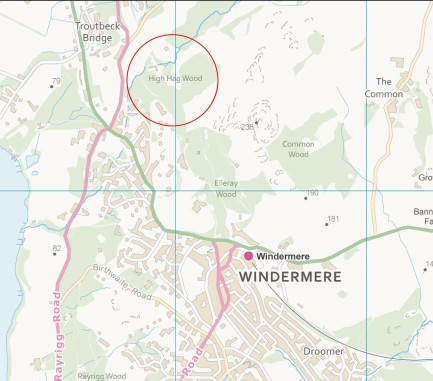

This is the third of my posts on the mining sites we have explored and surveyed in 2013 for the Windermere Reflections Project, and it concerns the Fairfield iron mine which is located at the northern end of Grasmere.

In the late nineteenth century this mine, in tandem with the more northerly Providence iron mine, formed the contemporaneously worked Tongue Gill Mines. The mine exploited a north-west/south-east orientated haematite ore vein in the Borrowdale volcanic rock that dipped to the south-west. running through the area of Great Tongue on the western flank of Fairfield mountain.

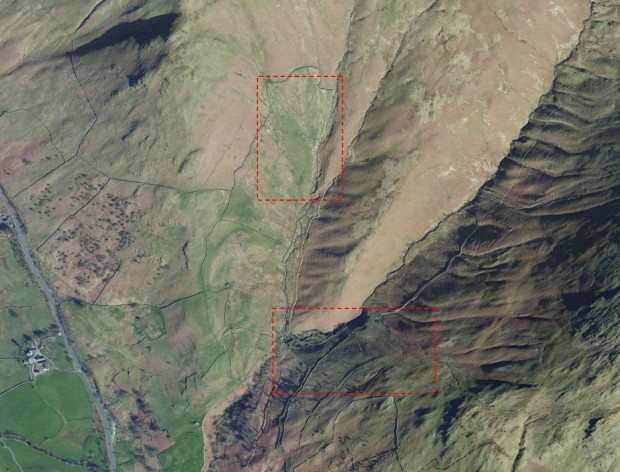

Location of Providence and Fairfield iron mines at Tongue Gill, near Grasmere

Google Earth image of Tongue Gill near Grasmere, with Fairfield and Providence iron mines highlighted

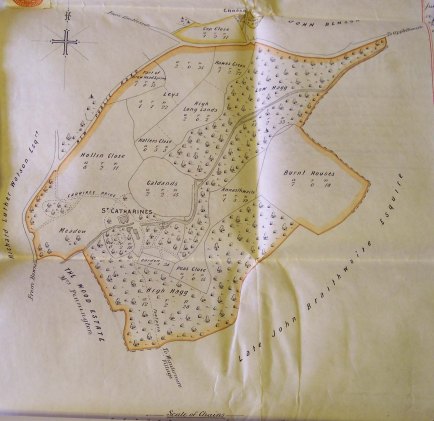

An agreement, dated 1693, to supply iron ore for nine years from pits in Grasmere (LRO DDSA 38/2)

The mining literature recorded both Tongue Gill mines as being worked around 1700 to supply ore to a furnace in Great Langdale. The only possible piece of evidence uncovered for pre-nineteenth century workings was an agreement dated 1693 which detailed Henery Rooper, a miner of Grasmere who was to supply Myles Sandys, of Hawkshead, (an individual associated with Cunsey Forge on the southern end of Windermere) with iron ore for nine years. No recognisable locations for the iron ‘pits’ in Grasmere were identified through the agreement and in any case the agreement was not enacted upon, but this surviving document may point to other such agreements/leases held in this period by other parties to mine iron ore in Grasmere. In addition, samples of haematite recovered at Cunsey forge during excavations undertaken in 2003 were consistent with known occurrences in the Grasmere area.

At Fairfield Mine, the mine layout is more complex than that at Providence mine which suggests some longevity of working although the documented history of the mine is relatively short-lived. Identifiable documents coincide with the 1870s boom in iron prices; in 1872 Thomas Dineen a man of Irish extraction, who was a rivet and bolt manufacturer and iron merchant from Workington, acquired a take note for one year with an option for a 21-year lease for the mine sett. His tenure was unsuccessful, indeed when he first visited the site in 1873 it was said that he couldn’t even find it.

Messrs Morgan and Waide of the Lake District Haematite and Mining Co. (© Rotherham Libraries, Museums and Archives)

On the 19th September 1874 the lease was taken up by the newly formed Lake District Haematite and Mining Co., that was set up by a group of Rotherham and Sheffield businessmen, presumably to feed raw materials for their other ventures. The mine agent 1873-1877 was John Hall, a skilled mining engineer from Alston. The directors included an alderman of Rotherham, James Clifford Morgan, and his colleague Francis William Waide, who were partners in the company of Morgan, Macaulay, and Waide a stove grate manufacturers, general iron founders and merchants, located at Baths Foundry in Rotherham.

The mineral statistics of 1874 show that 204 tons of ore had been raised, valued at £350 (along with the ore from Providence mine) but with the slump in the price of iron in the following year the mine was evidently in trouble. In total both Tongue Gill mines together raised 1,300 tons of ore (or 1500 tons in the other later secondary sources) in this short-lived period. By at least December 1875 the venture was in trouble and a pleading letter was sent by the company to the mineral agent asking for the unpaid rent on the mine to be waived due to the amount of development the company has undertaken on the mine.

The company failed to post accounts and a list of shareholders to the Register of Joint Stock Companies, as required by law. In 1877 the angry and unpaid chief mine agent John Hall took the named directors to court in Rotherham for unpaid wages and other liabilities. The directors counter-claimed that they had been conned into investing in a worthless mine, and eventually the company was liquidated. In part the fiasco eventually led to the financial ruin of Mr Waide but Alderman Morgan became mayor of Rotherham the following year followed by a comfortable retirement. The mine was recorded in the mineral statistics as being owned by the Lake District Haematite and Mining Co. Ltd from 1877 –1882 but it was standing idle.

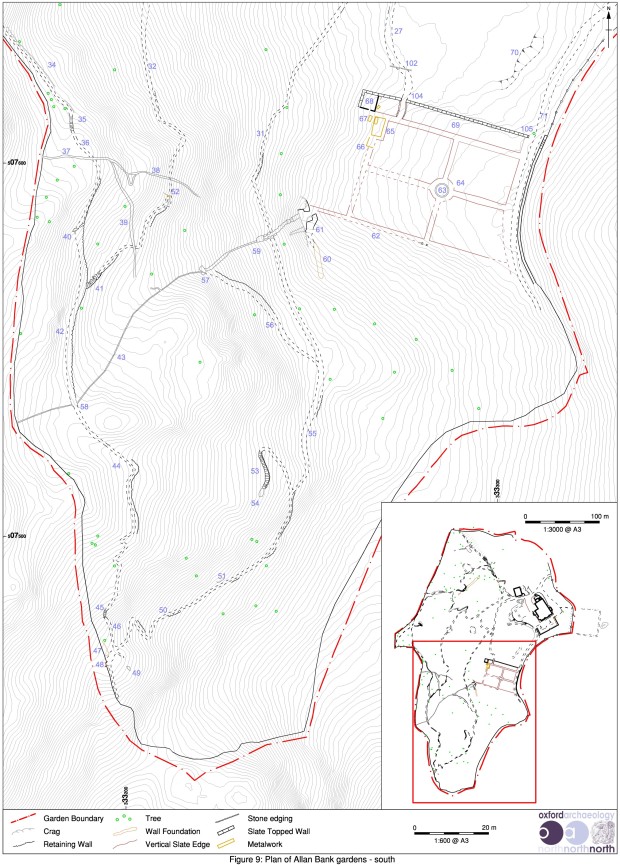

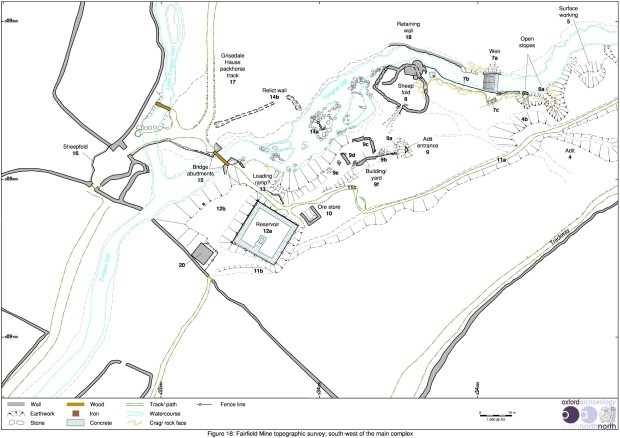

The surviving layout of the mine consists of three adits driven south-east into the hillside that run gently upslope following the course of the south side of Tongue Gill for over 150m. The ruins of mine buildings, and dressing floors/working areas are concentrated around the lowest adit on the western end of the site.

Overall survey drawing of the Fairfield iron mine, at Tongue Gill, near Grasmere

Some of the earliest mining remains surveyed at Fairfield comprise the series of well-defined earthworks of inter-connected hushes that run downslope from Rydal Fell to Tongue Gill. The main hushing runs south-east/north-west down to the gill and is partially overlain by an enclosure wall. There is a cross-cutting hush running along the slope that would have channelled water from at another hush and at least one hushed tributary stream. These hushes would have been used to chase surface evidence of the ore vein and to identify its orientation; it is possible that they predated the 1870s exploitation of the mine.

A linear hush running down the mountainside at Fairfield iron mine

On the edge of Tongue Gill, just to the west of the hushings, is a series of shallow surface trial workings running into the stream where ore nodules were visible in the stream bed and banks. There are two more pronounced deep cuttings running into the stream and the westernmost cutting is an almost vertical rectangular cutting which was either chasing the ore vein or has been stoped-out to extract ore near the ground surface.

The easternmost trial adit is potentially late-nineteenth century in origin, and there is a vertical quarried rock face on the footpath west of the trial adit where drill marks show it has been excavated using blasting technology.

The central of the three adits at Fairfield lay above the stopes and surface workings in the centre of the complex. The size of the spoil heap may point to this adit also having been purely a trial level.

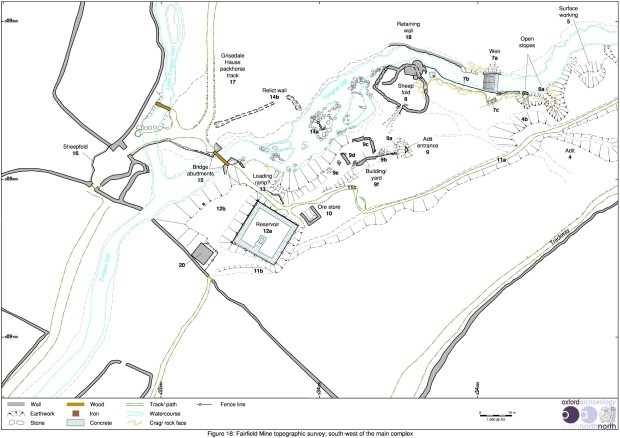

Survey drawing of the main area of working at Fairfield iron mine, at Tongue Gill, near Buttermere

The main focus for Fairfield mine is the lowest adit located on the western end of the complex. There are a series of features surrounding the adit, including a large spoil heap, a yard/working area and a possible ore store. The adit itself is partially blocked at the entrance and was not investigated underground. Tyler recorded that the adit was 6ft 6ins high by 4ft 6ins wide and extended into the hillside for over 160 yards before a roof collapse at the start of the stoping had closed it. A small trial of a subsidiary north/south orientated stringer of ore was recorded 60 yards from the entrance.

View along the top of the spoil heap/working floor at the lower mine adit of Fairfield iron mine

There is an extensive spoil heap running west from the adit entrance that spills steeply down onto Tongue Gill. The flat top would have been used for ore dressing and adjacent to the adit mouth is a partially collapsed rectangular year/storage area consisting of two short sections of walling. This yard has evidently not been roofed as a structure and here is a small gap between the yard and the retaining wall that define the south side of the working area which would have originally provided a gap for narrow gauge rails to pass by. At the southern end of the spoil heap are fragmentary remains of a walled loading ramp/bay, similar to that at Providence Mine and adjacent to it is a collapsed ore store.

A loading ramp on the southern end of the lower spoil heap/working floor of Fairfield iron mine

On the westernmost edge of the complex is a roofed bothy structure located adjacent to an enclosure wall at the entrance where an access trackway would originally have extended up to the mine. The bothy should probably be associated with miner’s accommodation/shelter as it evidently predated the construction of the nearby reservoir. Other features to note are the trackways running through the complex and the large bridge piers constructed across Tongue Gill.

A large uncovered reservoir built for Grasmere Urban District Council, was constructed on top of the mine complex but apparently does not seem to have done much lasting damage to the site. There is an associated weir located upstream on Tongue Gill where water was piped down to the reservoir.

View looking west downstream at the lower workings of Fairfield iron mine

The character of the working at Fairfield and Providence is comparable to the other boom period mining sites. Both Providence and Fairfield mines reflect a brief period of intense mining activity fuelled by high prices for ore, and accords with a number of other operations elsewhere in Cumbria. The decline in both cases was prompted by the slump in iron ore prices in 1875, and that was in itself prompted by the over production of iron ore across the region. Being operational for only a few years they demonstrate single phase integrated workings and as such provide an opportunity to examine the workings process of the late nineteenth century. The extensive hushes, small stoped workings and surface extraction at Fairfield iron mine may, however, have been undertaken in an earlier undocumented period of activity.